Marcellus shale

From Wikimarcellus

| Revision as of 05:55, 29 October 2009 Tcopley (Talk | contribs) (removed stub) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 23:42, 8 November 2009 Tcopley (Talk | contribs) (→Resources - added API video) Next diff → |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

| ==== Resources ==== | ==== Resources ==== | ||

| - | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcellus_shale -Wikipedia.org on ''Marcellus Formation''] | + | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcellus_shale -Wikipedia.org on ''Marcellus Formation'']<br> |

| + | [http://www.api.org/policy/exploration/hydraulicfracturing/hydraulicfracturing.cfm -American Petroleum Institute video on ''Horizontal drilling And Hydraulic Fracturing''] | ||

Revision as of 23:42, 8 November 2009

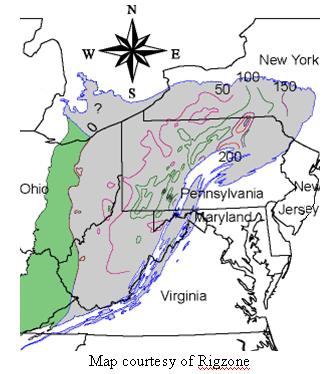

The Marcellus shale formation is a marine-sedimentary, rich-organic layer of black-shale rock. It is found deep underground in an area covering approximately 65,000 square miles and stretching roughly 600 miles from southwestern New York to West Virginia and includes parts of Maryland, Kentucky, Ohio and Virginia. It is very high-quality source rock. The thickest portion of it is located in eastern Pennsylvania and southern New York with a thickness of up to 250 feet or more. The main area of the formation is around 18 million acres. It is named for an outcropping near Marcellus, N.Y.

Gas in the formation is found in pores of the rock so tight that it is released only very slowly or else the gas tightly adheres to the rock. Both conditions may be true.

The Marcellus shale has three main sub-divisions:

- Cherry Valley Limestone (differently named in various locations)

- Oatka Creek Shale

- Union Springs Shale

These layers of rock have different organic contents as well as their own separate thickness characteristics due to the way in which the shale was originally deposited and over time eroded.

It has been known for decades that this layer contained gas, but until recently it was not believed economical to extract. Recent improvements in technology such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing of the shale have somewhat changed its economics. When these developments were combined with the comparatively high prices of natural gas during the first half of 2008 the endeavor appeared profitable for all of its participants. Earning a reasonable return on investment may now prove more elusive since natural gas prices dipped under US $8 per MMBTU for most of the second half of 2008, and were under $5 during the first quarter of 2009. Prices hovered under $4 for much of Q2 2009.

Recent estimates have ranged for between 50 and 500 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas that could be produced from the Marcellus shale. As more and more favorable drilling results become available to benchmark estimates, forecasters have grown increasingly confident about making projections closer to the high end of this range. 500 Tcf would be enough gas to supply the U.S. for about twenty years at the present rate of consumption.

In some areas of the formation, natural gas fractions are also present such as butane, ethane, and propane.

Pennsylvania has around one half of the proven U.S. natural gas reserves. The proximity of most of the deposits to the natural gas consuming cities of the east coast makes the Marcellus an especially attractive target for exploration.

The Marcellus shale formation is usually found at a depth of 5,000 to 8,000 feet, but can run as deep as 9,000 feet. Pressure gradients range between .40 to .58 psi.

Marcellus shale drilling rigs are roughly twice the size of ones used for shallow wells. They are usually around 150 feet high, with an equipment platform 20 feet off the ground. Horizontal drilling rigs are bigger still requiring larger horsepower engines to drive the drill bits further along.

The production of a typical shale gas well drops off significantly after the initial year or two and then slowly declines after that over its full lifetime.

In the industry, it is known as an “unconventional deposit.”

One method of prospecting for gas, not only in shale formations but also for gas found within deeper structures below, is to use seismic waves to map out the underground location of deposits.

Exploration typically begins with vertical wells. If natural gas is found in commercial quantities and grade then the initial production can help fund later horizontal drilling.

When gas shows are spotted in traditional source rocks then it merits further investigation. This may consist of reviewing existing data from the well, examining core samples and analyzing other information.

If the results of the preliminary investigation look promising then vertical wells are drilled to locate the most prospective part of the formation and confirm the characteristics of the reservoir. Analysis of seismic data also plays a role.

If all looks good, then horizontal drilling may be undertaken.

A horizontal well bore has the benefit of intersecting more of the shale and producing far greater amounts gas once it is hydro-fractured.

Resources

-Wikipedia.org on Marcellus Formation

-American Petroleum Institute video on Horizontal drilling And Hydraulic Fracturing